Beginner's mindset - bringing it into Innovation

3 new ways to look at being a beginner by a actually being one: whether you're a substack creator, an Engineer, a Finance guy, a Developer, a PM or just somebody wanting to innovate!

Happy Wednesday! 👋 I’m Francisca and I’m happy to visit your inbox today for insights about Innovation, and how to bring your ideas to life. Today, let’s dive into some practical, actionable ways to learn by doing - a beginner’s mindset is not a bad thing to have!

Whether you’re an engineer, a seasoned manager, or an independent creator, stepping into the shoes of a beginner can open up new opportunities for growth, collaboration, and innovation.

Last Sunday’s post it was about the book Beginners and the movie The Intern.

I’m not going to repeat anything from that post, but rather, suggest some actionable ideas for you to get started!

We’re all something at work, right? We’re experts in what we’re paid to do at work, whether that’s being Product Managers, Developers or Engineers, others might already be Middle Management or Directors.

So, independently of that area (where we were beginners sometime ago) you all bring a specific skillset to work. Sometimes, you might be facing a challenge that is beyong your skills: you have an idea you want to pitch, get buy-in, eventually budget to have that idea see the light of day! And you feel like “fish outside of water”, outside of your usual skillset. Well, you can learn how to do it well!

Here are some distinct approaches to take that beginner’s curiosity and put it to work in your professional life.

1. Weekly Failure Meetings

Start-ups thrive on experimentation, and not every attempt works. Examples like Google Labs show that you can include that “start-up approach” inspire corporations.1

Adopt this culture by organizing a "Weekly Failure Meeting," where your team shares small failures. Celebrate the lessons learned rather than shying away. Engineers could share prototype attempts that failed, and if you’re a Substack creator you might talk about a post that didn’t get the response you expected!

Why does this matter?

Because how we generally think about failure or being a beginner is not a healthy or good approach. We usually fear failure.

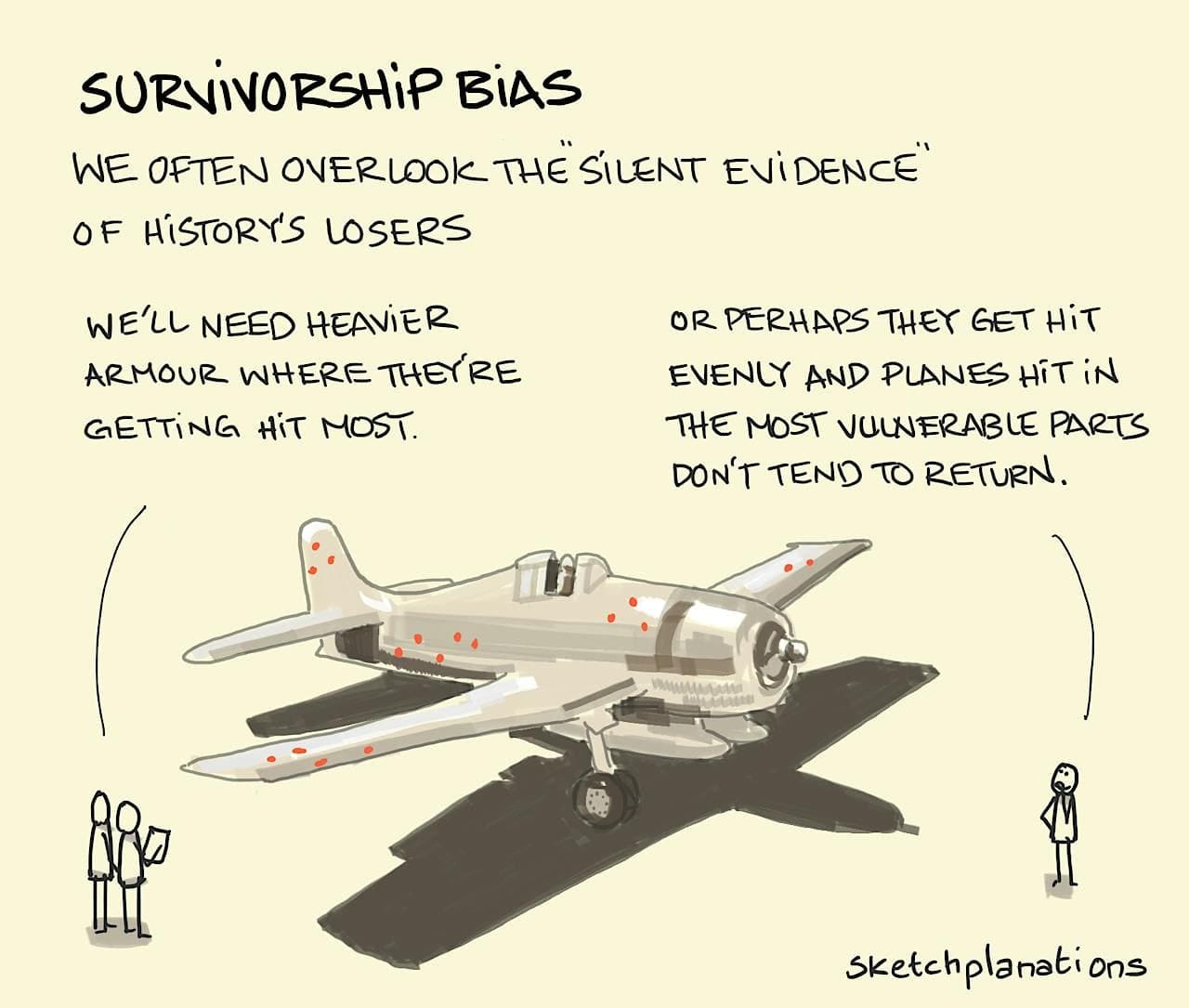

Connected to this, somehow, is a very famous example of bias. Specifically, survivorship bias comes into play here: a concept best illustrated by an old wartime story.

During World War II, engineers analyzing bullet holes on returning aircraft initially thought they should reinforce areas with the most visible damage. But then a statistician named Abraham Wald flipped their thinking: the planes that survived had damage in non-critical areas, meaning the critical spots were on the planes that never made it back.

By studying the "survivors," they nearly missed the real lesson. The invisible failures—the planes lost in combat—actually held the key to making stronger, more resilient aircraft.

We think failure is bad, but how many failures ended up saving lives once we applied the lessons learned?

How much of survivors (good ideas) are we using to cloud our judgment, leading us to think that inevitably the failures are bad, forgetting that failures also allow us to move forward?

To this, I challenge you with one of my favorite books to reframe failure: Amy Edmondson’s Right Kind of Wrong. Edmondson was a PhD student and she had joined a team to study medication errors at Harvard Medical School.

How she looked at the things initially, and all her study, failed entirely. Instead of abandoning her work, she learned to see failure as a critical part of understanding complex problems. Edmondson came to understand that if you're not facing failures, you're probably not breaking new ground. And that’s how she eventually pivoted to what has made her who she is today!

Take it from her directly (I’ve bolded the passages I liked):

But suddenly, this did not seem an auspicious beginning to a research career. I had unequivocally failed to support my hypothesis. I had predicted that better teamwork would lead to fewer medication errors, measured by nurse investigators stopping in several times a week to review patient charts and talk to the nurses and doctors who worked there. Instead, the results were suggesting that better teams had higher—not lower—error rates. I was not just wrong. I was completely wrong. (…)

I would also begin to understand how success as a researcher necessitates failure along the way. If you’re not failing, you’re not journeying into new territory. Since those early days, in the back of my mind, a more nuanced understanding of terms such as error and failure and mishap has taken shape. 2

I can even bring you my own examples:

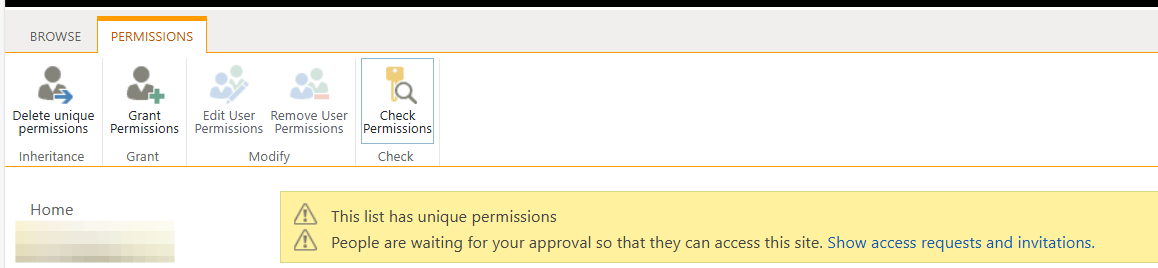

My biggest failure that was visible for everybody was on my second or third week at work in my former job. They asked me to do something in a platform I had absolutely no training on, other than understanding the basics of it. They gave me basic instructions for a basic task: create a new list and share it with HR ONLY.

Somehow, while doing so, I was actually able to share with HR only… but I also single-handedly changed ALL organization’s file sharing rules to have HR group with access by default - and surpass all other prior permissions to all files, sites and pages!

Basically, I clicked wrongly on this menu…

Lesson: do not click on delete unique permissions unless you’re absolutely sure!

We’re talking about an Intranet (that means: private network contained within a company that is used to securely share company information and resources among employees) based on one SharePoint site and many sub-sites, with more than 340 people accessing it for work and other purposes, such as onboarding. And I basically removed ALL their settings from file sharing, so all the files got back to square 0: as I removed everyone’s unique permissions.

Luckily, my manager at the time was also very understanding and she understood that she should have given me more guidance. We went to the backups (3 days old), and were able to rebuild most of it. But sometimes we still found that pesky HR group in random spots :) Even 9 months later! While we were worried and annoyed when it happened, we also laughed about it later on.

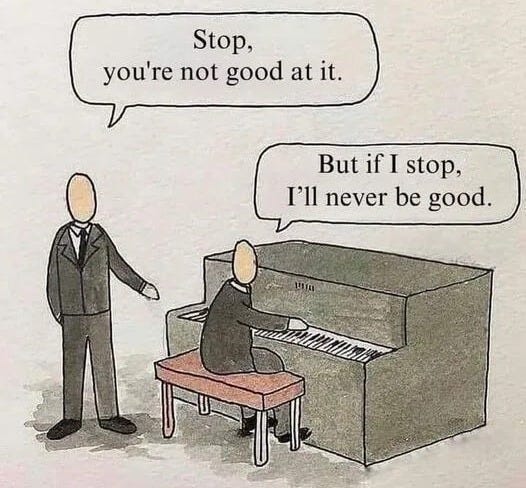

Why do I talk about it now? Because this is a great example that beginners will commit mistakes - big ones even, if given the chance. Not because we want to… but because it happens.

Think of a baby (one of Vanderbilt’s examples from his book): how many times will the baby fall on the floor when trying to give the first steps? We don’t make it seem like a failure, right? We encourage the baby to try! Same with riding a bike, or learning how to drive. We are supportive!

If you can talk about the mistakes, though, you are going to learn more. And if you can come clean about them, and feel safe asking for help, it’ll be better than hiding the mistake altogether.

So think of this activity as an opportunity to create an open culture where failure is not “finger-pointing” but rather a learning opportunity for all.

Imagine I never wanted to have anything to do with SharePoint anymore, due to feeling shame or feeling I wasn’t made to take care of that type of platforms?

One of my many tasks at my current job is managing our team’s (new company) SharePoint, with a rather complex and diverse structure. A skillset I acquired and I’m extremely confident doing, because I learned from mistakes, I ask for help when I’m unsure (Google also counts as help) and I learned confidently, while acknowledging mistakes and all!

2. The 1-Hour Deep Dive Challenge

Set aside one hour each week to explore an unfamiliar topic. Maybe AI, SEO, or even digital art—something out of your comfort zone. Something you can benefit from (at work), for instance, but is not directly connected to what you do. You can even invite colleagues from different departments to join in.

This cross-functional curiosity keeps learning fresh and challenges your assumptions.

You can also have this to generate collaboration among peers that wouldn’t traditionally collaborate. Or you can have them be the experts teaching you!

I personally have been taking free and paid courses to go outside of the comfort zone - I’ve been focusing specifically on AI, LLMs and might start machine learning soon! I also have been learning how to draw on Procreate and how to write newsletters on Substack, as you can see/read!

3. Challenge Your Own Content

This one’s great for the Substackers!

Take a beginner’s approach to something you’ve done in the past…

For instance, take an article you wrote, a presentation or product review you made a year ago, or a code snippet you created.

Now, ask yourself how you would do it today, with no preconceptions. How can you simplify it, make it more engaging, or adapt it to new trends? This constant re-evaluation and re-imagination keeps your work dynamic.

If you draw: how would you draw it today? Maybe some different way of putting the shades? Or using different materials altogether?

If you’re an astrologist, how would you look at those constellations today?3

If you usually like to sing: look at songs you used to sing and evaluate how your signing and breathing has changed and how you would breathe in those pauses?

Turning Curiosity into Action: key takeaways

The key to inspire or spark innovation is simple:

Keep being curious, and keep taking small steps forward, even if they are outside your expertise.

The beginner’s mindset is more than an abstract idea or a shiny name: it’s something that you can practice every day, whether that’s through a deep dive into something new, experimenting with AI, or taking on a micro-project.

The consistent habit of approaching the unknown with curiosity, rather than fear, is what helps us stay innovative!

Which of these ideas are you most excited to try?

Mine has definitely been the 1h (I make it 4h weekly), I’ve done so many things lately! It’s so good to be a beginner!

One of the examples is watercolor - yes, this is unrelated to innovation, but it helps to make the point that you should do this “being a beginner” often!

Here’s the takeaway:

1. Not all mistakes or failures are terminal. You can roll-back, you can go to the back-up, you can jump to the last version.

> When in doubt: back-up.

> When in doubt II: ask for help.

2. There’s a lesson in every failure. If you’re open about it, you’ll learn, and so will everybody else, so mistakes are not repeated.

3. It's okay to be a beginner. Otherwise, how would you become an expert eventually?

4. Find ways to be a beginner at work and in life! You can learn a lot and it can be transferrable to other things you do!

5. Something as short as one hour a week to learn a new skill can compound well! 52h in a year is better than 0! Imagine what 52h of learning SQL or AI can do to you and your future work skills!That’s it for a Wednesday!

I’m heading off to Copenhagen for a Hackathon later this week! Something I’m entirely a beginner in. It’s my second Hackathon ever, but I’m excited about it, even if I come back home with a failure story!

I’ll see you next Sunday, with a post talking about a very famous pop culture reference and what it can teach us about biases!

Highly recommend reading this to get inspired: The 30 Biggest Failed Google Products Up To 2024, https://www.failory.com/blog/google-failed-products. Last accessed November 12, 2024.

Edmondson, Amy. Right Kind of Wrong. New York: Atria Books, 2023.

Oh my...I almost did that with the lists in Sharepoint permissions a few years back. Thankfully I had someone over my shoulder and yell "STOP". We live and learn right...and innovate!

I love keeping the beginner’s mindset in mind. I try not to close myself off to learning by assuming I already know something.

I like the idea of specifically setting aside an hour a week to learn something you’re a true beginner at. It seems simple and like it would give a good return.

The key is to action on our curiosity.